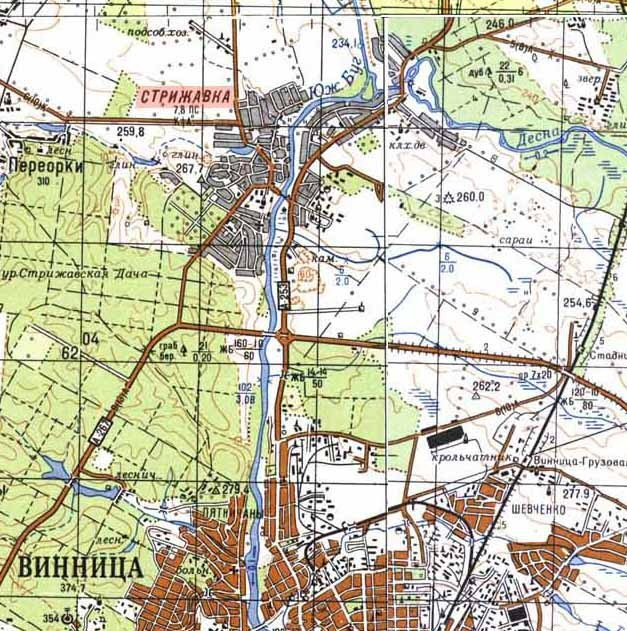

Strzyżawka

Pietniczany

2018-08-21

Strzyżawka is a locality splendidly situated on a hill, right where the mouth of a river named as the town, joins the Boh. According to 15th-century documents, kept before the 1st World War in the collections of the manor house, the description of the ancient settlement “Striżawka”, among other issues also named some Dmytro Strizhavskiy as the proprietor of surrounding lands at the time.

The same source claims that six or even seven Uniate churches were located there later, and a large Basilian monastery stood a verst from the town, on a towering granite rock protruding into the Boh river.

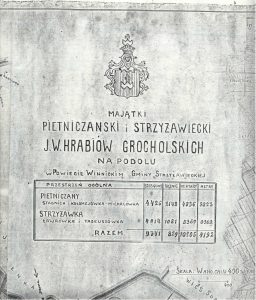

Dymitr Strizhavskiy was followed by the Lubomirskis and the Potockis as heirs of Strzyżawka. The property was purchased from Antoni Potocki by Michał from Grabów Grocholski, family crest Syrokomla (born 1705), (son of Ludwik, king’s cup-bearer of Dobrzyń and of Justyna née Leniewicz family crest Prawdzic), deputy hetman of Ukrainian party, district judge of Bracław, deputy to the Seym (parliament), founder of the church and Dominican monastery in Winnica (1758) and of a chapel in Tereszki. He originated from a family that had moved from the Sandomierz region to Volynhia as early as in the beginnings of the 16th century, and afterwards to Podolia in the second half of the 18th century.

Thus Michał Grocholski already had in his possession Hryców and Tereszki in Volynhia, in addition to Strzyżawka in Podolia. He also inherited Pietniczany and Woronowica in the Bracław district from his wife, Anna née Radzimińska family crest Lubicz, daughter of Michał (esquire carver of Czernichów) and Małgorzata Kamieńska, family crest Ślepowron. The properties had passed over to her following the heirless death of her only brother, Marcin Radzimiński. Hence the fortune of the Grocholskis was again very importantly increased. In spite of the excessive debt borne by both the Pietniczany and Woronowica keystones, as a result of many years of efforts they were freed of pledges and liabilities.

Michał Grocholski from Grabów split his extensive Volynhian and Podolian estates between two sons, attributing Strzyżawka and Pietniczany in Podolia, plus Hubcza in Volynhia to Marcin, voivode of Bracław, Knight of the Order of St. Stanislaus, and the remainder to Franciszek, Grand Sword-Bearer of the Crown.

Voivode Marcin Grocholski (1727-1807), married to Cecylia née Chołoniewska family crest Korczak, daughter of Adam and Salomea née Kątska family crest Brochwicz, apart from properties inherited from his father, also possessed Hryców, Sabarów, Soroczyn, Stepanówka, Woronowica, Sudyłków, Kołomyjówka, Michałówka and Stadnica. He split the extensive properties between five sons, of whom Jan Duklan received Sudyłków, Michał, starost of Zwinogród – Pietniczany, Ludwik – Hryców, whilst Adam fell a hero’s death fighting in Kościuszko’s army in the battle of Maciejowice. Strzyżawka was attributed to Mikołaj Grocholski, marshal of gentry, later governor of Podolia.

Mikołaj Grocholski (1782 – 1864), married to Emilia née Chołoniewska, left the most permanent mark in the history of Strzyżawka, by founding there a Catholic church and a palace. In addition, he also contributed a convent for the Nuns of the Visitation in Kamieniec Podolski.

The only daughter of Mikołaj and Emilia Grocholskis – Maria, having married Wojciech Dzierżykraj – Morawski family crest Nałęcz, contributed as dowry i.a., also Strzyżawka. When Maria Morawska née Grocholska died in her youth, and the widower was ordained, Strzyżawka was inherited by the youngest of three sons: Józef Dzierżykraj – Morawski.

During the brief time when not owned by the Grocholskis, both the residence and the Strzyżawka properties suffered great neglect, for their owners lived elsewhere. Józef Morawski even decided to sell the property. Under the laws then in force in so-called “taken provinces”, the new customer could be a Russian only. Hence the issue became notorious, provoking lively protests in Poland. Then Morawski’s cousin, Tadeusz Grocholski, until then studying his favourite art of painting in Paris, under the tutorship of the well-known portraitist Leon Bonnat, quit studying and came back home, to save his patrimony threatened by alien takeover. Since the normal purchase by a Pole was then impossible, a conclusion by both parties of a 16-year lease contract was agreed, a move actually tantamount to sale and purchase.

Tadeusz Przemysław Michał count Grocholski (born 15 V 1839 in Pietniczany – died 29 VII 1913 in Strzyżawka), son of Henryk and Franciszka Ksawera née Brzozowska family crest Belina, married to Zofia countess Zamoyska (1865 – 1957), daughter of Stanisław and Róża née Potocka, energetically undertook to refurbish the property.

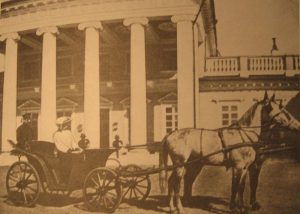

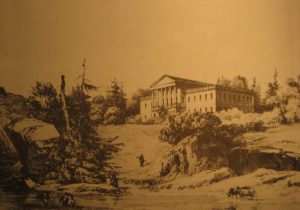

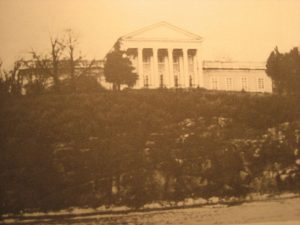

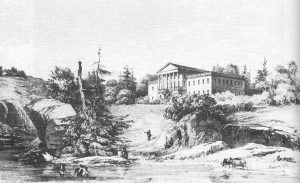

Its size is told by Edward Chłopicki, who visited Podolia in 1875. Although he marvels at the beautiful location of the palace, standing on the top of a rock covered by giant trees and dominating over the surroundings by the towering colonnade of its gallery, his impression nevertheless diminishes as he comes closer to the area. For he noticed traces of complete neglect, made evident even by the “chipped” entrance gate.

Despite the deplorable condition of Strzyżawka, both the estate and residence,

Tadeusz Grocholski still had to wait several years to start reconstruction. For exactly when he took over the estate in 1877, the Tsarist authorities used the entire building to house a hospital for wounded enemy POWs, arriving from the area of the Russo-Turkish war. Only in the 1880s the task of restoring the beautiful edifice, at the time full of rubble, dust and vermin, could be launched. On rebuilding Strzyżawka, Tadeusz Grocholski was simultaneously forced to struggle for 30 years both against Józef Morawski, who having wasted another property, later demanded additional payment, and Russian authorities, striving to oust him from Strzyżawka. He ultimately prevailed in the struggle only when a friend from his young years – minister of court, baron Frederichs – intervened to the Tsar. Working to bring back to life the estate and residence, Tadeusz Grocholski also dedicated much time to social activities, i.a. as vice-chairman of the Podolian Agricultural Association, and jointly with his brother Stanisław, he organised a peasant bank, etc.. He also engaged in painting. Genre, religion and portraits were his favourite topics. He also copied masterpieces of European art.

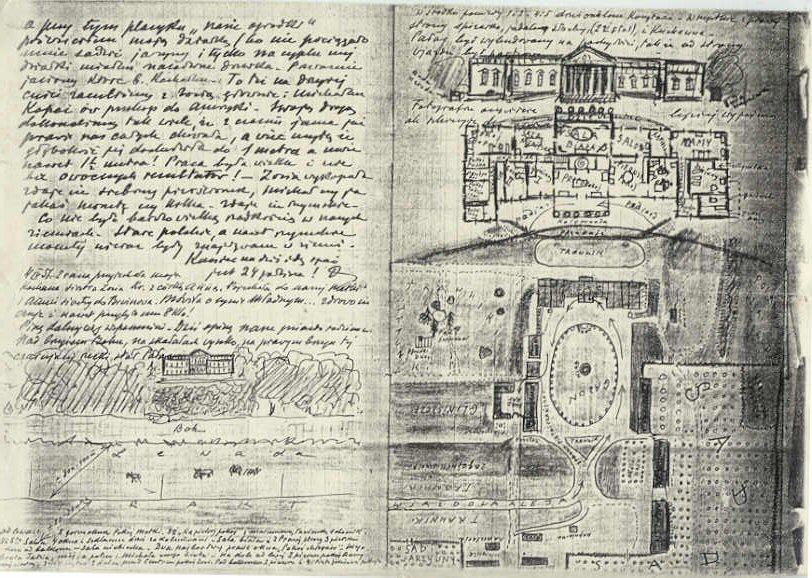

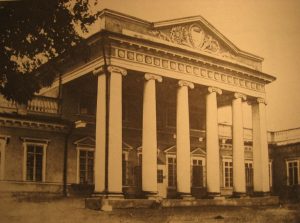

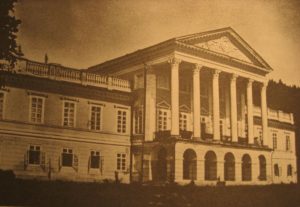

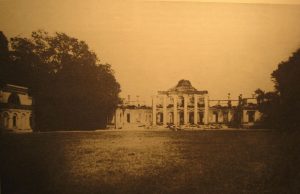

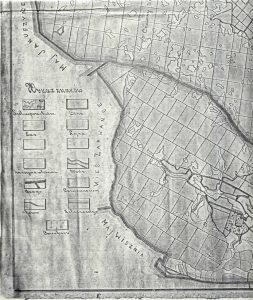

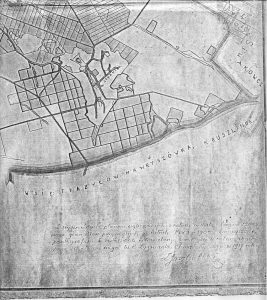

The Strzyżawka palace, erected by Mikołaj Grocholski in 1806 – 1811 according to the design by a – regrettably – unknown architect, stood – as mentioned – on a high stone rock, right by the Boh river, within an extensive landscape park. From the road, planted at both sides with tall poplars typical of areas adjacent to the Vistula river, leading from Winnica to Kalinówka and further to Koziatyn and Berdyczów, the manor house was approached turning to the left, through a high long bridge over the Boh river.

The road led farther towards a quite elevated hill, on which a Catholic church stood on the right side, manor building at the left, together with a garden surrounded by a high wall. Then by turning twice at right angle, through an avenue of old lime, the palace forecourt was entered. At the right side a storehouse and granary were passed by, then an orangery and barn with a vegetable and fruit garden right behind, while the left side featured a woodshed, stable, coach house, annexe and the so-called “old kitchen”.

The palace, standing directly opposite the exit of the avenue of lime, at the other side of the great rectangular forecourt, was based on a plan of short horseshoe. From the western side, that is from the driveway, it was a one-storey building, with five-axial middle parts elevated by a low floor, two-storey from the eastern side, also with a small floor. The fifteen-axial façade of the palace was dominated by a six-column portico in grand order, located at the two-storey section. All columns, situated on a low terrace, were provided with Ionic heads. However, the extreme ones had a square profile, the remaining – circle. Columns supported the beam structure, surrounded from the base by a wide profiled cornice, and by a frieze composed of rosettes in the middle, but only from the front. The whole portico was encircled by a crowning kragstein cornice. It is closed by a rectangular break wall, bended in the middle by an obtruse angle, that features mouldings depicting cornucopias, plant twigs and rosettes, and against their background an oval coat of arms surrounded by a Syrokomla laurel wreath of the palace’s founder, and Korczak of his wife. Above them a nine-rod count’s crown was added later. The main entrance doors with narrow frames and four windows split into ten plots, comprised by the frames of the portico, had triangular pediments based on brackets, while the windows of the small floor had only frames with subtly accentuated benches. The storeys of the portico section were separated by a smooth trim. Above it was a row of short kragsteins, supporting a narrow balcony. The ceiling of the portico was divided in five fields and adorned with large rosettes. The artistic decor of the two-axial side wings, as well as of the triaxial section of the elevation between them and the portico, did not differ much from the furnishings of the two-storey section. Only the windows – of identical shape and size – were provided with level pediments instead of the triangular type, also based on brackets. The smoothly plastered walls were crowned by a kragstein cornice.

The eastern façade, facing the Boh river, was much more grandiose. Although it lacked side wings, nevertheless it was accentuated on five central axis by a wall break with three-storey portico, split by Corinthian pilasters.

Corinthian columns in good order, were based on arcades covered by rusticated plasters, situated by the ground level.

The terrace over the arcades was surrounded by a balustrade of wrought iron. The decor of the section – with wall break with corners comprised in pilasters – resembled the decor of portico facing the driveway. Only the windows of the middle storey were replaced here by French windows, facing an extensive terrace under the colonnade, from where the especially appealing view to the area overflown by the river and the more distant areas, was admired. The garden portico was crowned by a triangular frontage, surrounded by kragsteins. Its tympanum was also covered by mouldings with a main motif of an oval coat of arms. The ground level part of side sections with smaller windows split into eight plots, had fluted plaster, while the upper storey – smooth. Similar was the appearance of triaxial side elevations, the southern and northern. Storeys were separated by horizontally smooth doubled trims, and a narrow cornice running under the parapets of the windows of the high ground floor. All façades were crowned by a kragstein cornice. The central section of the palace was covered by a smooth, shingled two-pitched roof, while side parts – by a levelled three-pitched roof, hidden behind a railing parapet that surrounded the whole building.

The structure of the main dwelling-representation storey after reconstruction continued as two-sectional, but quite complicated, unsymmetrical, with many narrow corridors, entrance halls, bathrooms etc.. Also, the decor of specific rooms was diverse, from modest to exquisite. All featured smooth parquet floors, mostly made of several types of wood, laid into geometric patterns. The high two-winged panel door was covered with white varnish or dark French polish. Upper and lower panels – comprised in frames – were adorned by sculptured oval wreaths. In many rooms ceilings were supported by bevels or kragsteins. Some stoves had original, rarely seen shapes.

The entrance to the palace interiors led through a large hallway receiving light through two windows. Right here, opposite the entrance, glassed doors were located with spiral stairs behind, leading to the ground level section, or to the first floor. Hunting trophies hanging above the doors in form of boar head, old harquebuses, javelins, hunting horns, etc.. A clock was nearby, regulating the everyday life of the entire household. Paintings depicting “still life” were hanged above two low stoves. One of them featured roses, the other – fruits. The left wall was adorned by portraits of Michał Grocholski and his wife Anna née Radzimińska, by an unknown author. Regarding furniture, the hallway comprised two trunks, of which one, closed for the day, at nighttime was used as a bed for the Cossack on duty. On the second trunk situated in the middle, there was a wooden box with draughts, destined for the entertainment of Cossacks stationing in the palace. Other furniture, specifically benches and heavy oak chairs, originated from the farmhand school in Podzamcze, estate of the Zamoyski family.

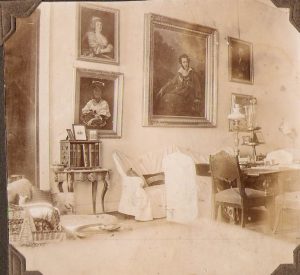

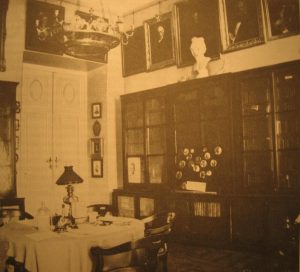

From the entrance hall to the right the so-called “first room” was entered, in which one window was yet comprised by the portico, while the second – in the ground floor section. The room, with ceiling on bevel and floor laid in small squares, in a bright colour scheme, was used as a library. Therefore, standing aligned along the walls there were not very high glassed cupboards with books, while above them all free space was occupied by family portraits and miniatures.

The middle of the room featured a table with rounded corners, covered by green cloth, and chairs with bended handrails. An Empire chandelier was suspended on the ceiling, made of bronze. White marble busts stood on cupboards.

Directly adjacent to the library was the two-window house master’s room, of identical shape and size. A narrow, reconstructed corridor running across the palace, already in its extended wing section separated the building’s central section from four rooms aligned along its southern wall.

The former two rooms situated at the left side of the hallway, corresponding to the library and the house master’s room, were transformed into three smaller guest rooms. Also, the whole left wing of the building was split.

The representative row, with enfilade door composition, was located in the eastern section, affected by changes to a much lesser extent.

The whole middle was occupied there by a big ballroom protruding with a wall break, called “white” due to its walls covered by white, polished stucco.

It was rectangular in principle, but its interestingly designed ceiling gave it an oval appearance. The central, triaxial part of the room was two storeys high with a flat ceiling. Above three French windows to the terrace, the upper part also included three square windows. Both side parts had semicircular vault without upper windows. The central flat ceiling was adorned by a large rosette, while four rosettes were much smaller. All made of white stucco. Semicircular vaults were covered by mouldings in form of plant grotesque, also with rosettes, comprised in wide, smooth frames shaped as trapeziums. The beam structure and bevels of the vault, composed of frieze also depicting plant grotesque, were based on a profiled cornice, and inserted into a kragstein cornice from the upper side. Beam structure was supported by four semicircular Corinthian half-columns. A large rectangular field above the kragstein cornice, opposite the upper windows, was filled by a stucco composition, apparently depicting images of life in ancient ages. Both internal corners of the room were decomposed by two panels, framed on sides by pilasters, connected at the top by semicircular profiled cornices. The floor was composed of a geometric pattern.

The “white” room eventually was not fully completed by the founder of the palace. For example, it lacked a fireplace, proper chandeliers, for which rosettes in the central ceiling were prepared, and wall lamps. The deficiency was complemented by a huge chandelier for 365 candles, inventively made of several wooden hoops of various sizes, varnished in white, covered by goldened iron leaves. The chandelier was made by a local home carpenter according to the idea of Stanisław Grocholski, as a wedding present for his brother Tadeusz, who married Zofia countess Zamoyska. The hall was never provided with adequate furnishing. It comprised huge late-Biedermeier mahogany sofas standing in corners, plus tables and chairs in the same style, in front of them. The latest function of the “white” hall was to host family life. Breakfasts, lunches and dinners were eaten here, and homework done with children. An old piano was also there.

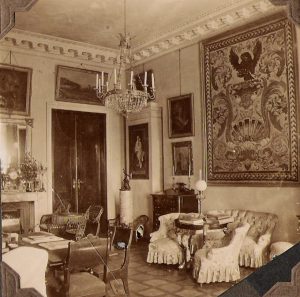

At the northern side of the ballroom there was also a rectangular, but much smaller “blue” room with three windows. It was entered through darkly coloured doors, richly decorated with intarsia.

Its name was due to the walls in that colour, covered with stucco. The ceiling of this room was covered by white mouldings. The floor also had a geometric pattern, but differing from the “white” hall.

Two corners opposite to the windows comprised vaulted alcoves with square stoves inside, composed of two storeys: upper of larger profile, and lower of smaller profile. Both crowned by big vases with handles. Movable furnishing of “blue” hall was composed of a table, sofa and chairs made of mahogany.

A huge, old-fashioned billiard stood in the middle. This room was seldom used. The corner northeastern room was used as a living room, others likewise, situated along the northern wall as well.

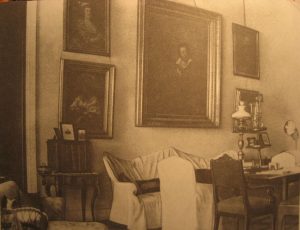

Another door as beautiful as the one to the “blue” hall, also led from the “white” hall to the southern direction to the adjacent salon, that was not given any name. Its ceiling was supported not on a bevel, but on a kragstein cornice, inserted at top and bottom into narrow trims of mouldings “in crop eyes”. It featured two in-wall rectangular stoves, crowned by profiled cornice, covered by a dark painting with figural motifs, and a classical fireplace from white marble, adorned with low reliefs and bronze. The floor was composed of large, bright squares, comprised in narrow, dark frames.

A bronze, cristal chandelier was hanging from the ceiling adorned by a small rosette. Furnishing was mainly composed of soft, upholstered furniture from the late 19th century, plus several mahogany drawer chests and cupboards. Prominent among those was a console between windows, original Boulle and a small table Louis XV-style, richly adorned with intarsia and ornamented with bronze.

Also many works of art were located in the salon. A top place among them fell to the portrait of Mikołaj Grocholski, founder of the palace and church, painted a la Byron by Józef Oleszkiewicz. A large part of another wall was occupied by a large 16th-century Italian embroidery, made on silk linen. Its pattern represented a black eagle with spread out wings, holding a crown in his talons. Below, among stylish plant motifs, a mussle was visible among fruits. The embroidery was received by Tadeusz Grocholski from his mother Cecylia Chołoniewska, superior of the nuns of the Visitation in Kamieniec Podolski. A painting by Rosa Bonheur, Orka (Ploughing), was hanging above the door leading to the library room.

By the side, on a column stood the bronze Michał Archanioł strącający smoka (Archangel Michael Casting Out The Dragon), and on a console situated between windows, a bust of Julia Poniatowska (née Grocholska) made of white marble, regrettably the sculptor is unknown. A mirror in goldened frames was hanging above the fireplace. The fireplace’s cornice was decorated with an 18th-century clock in goldened bronze frame, plus candelabrums made of a similar material.

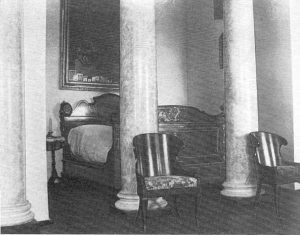

On the side of the salon there was a one-window room, called bath. It comprised a large marble bathtub. The room was used as a connection from the salon to the corner southeastern salon, with walls covered by uniform celadon stucco, functioning as the bedroom of the lady of the house. Four Ionic columns stuccoed to the same colour, but slightly veined, supported by black square bases, separated one third, rear part of the room from the frontal section, thus creating a bedroom.

The ceiling, decorated with mouldings, was supported on a bevel composed of cubic cornice framed by slats “in crop eyes”. Several dozen centimetres below, the room was encircled also by a wide profiled cornice, also with side bands “in crop eyes”.

A fireplace of white marble was located at one of the side walls. The parquet floor had a pattern. During the reconstruction of the bedroom, its architecture was partly altered by the separation of the rear part to create a narrow corridor, that started at the frontal living room of the master of the house.

The house masters gathered many precious elements also at this place. Such as the big Boulle bed situated in the bedroom, donated by princess Maria Czartoryska née Grocholska to her brother Stanisław. Above it, there was an embroided Gobelin picture in golden frames, representing Wniebowzięcie Matki Boskiej (Assumption of Virgin Mary), made by the nuns of the Visitation in Kamieniec Podolski. In addition, the room was adorned with several other paintings as well. As for furniture, there were yet two ebony wardrobes with bronze ornaments, a large mahogany desk, small round tables and Empire mahogany chairs, upholstered with damask in flower pattern. A bronze head, assumed likeness of Orlątko (Eaglet) was put on the fireplace, in addition to bronze candelabrums, representing kneeling angels holding vases in their hands. They were meant to create the impression to be pouring olive to lamps.

On the low floor, from the side of the frontal portico there was a rectangular room in the middle, with three windows and door to balcony, with two one-window rooms on the sides, used as living rooms. All modestly furnished, arranged to be comfortable and modern.

The Strzyżawka palace also housed many works of art, gathered mainly in representation rooms, that nevertheless were moved from time to time. Especially interesting was the gallery of paintings on various topics, albeit dominated by portraits. Apart from the already mentioned, the gallery boasted the following: Portret mężczyzny w krezie z koronkami (Portrait of a Man in Ruff with Laces) attributed to Van Loo, Święta Cecylia grająca na organach w otoczeniu aniołów (St. Cecilia Playing the Organ Surrounded by Angels) by Rubens, Matka Boska z Dzieciątkiem Jezus na rękach (Virgin Mary with Infant Jesus in Her Hands) by Carlo Maratta, Dama hiszpańska w koronkowym kołnierzu (Spanish Lady in Lace Collar) by Suttermans, and among portraits: of King Stanisław August (Marcello Bacciarelli), Katarzyna Chołoniewska née Rzyszczewska wife of Rafał (Józef Grassi), Marcin Grocholski, voivode of Bracław, and Cecylia Grocholska née Chołoniewska (Jan Chrzciciel Lampi Jr.), Franciszek Grocholski sword-bearer from Grabów, and Helena Justyna Grocholska née Lesznicka, wife of Franciszek (Józef Pitschmann), Jan Grocholski from Dukla, camp leader with grade of general, and Emilia Grocholska née Chołoniewska, wife of Mikołaj (by Reichel), Franciszka Ksawera Grocholska née Brzozowska, wife of Henryk (from a photograph), Tadeusz Grocholski of 1889, and of the same Tadeusz from a photograph, and of Zofia Grocholska née Zamoyska, wife of Tadeusz, painted by Kazimierz Pochwalski, portrait of prince Adam Czartoryski and a copy of Titian’s L’amour sacre et l’amour profane (Sacred and Profane Love) by Leon Kapliński, portrait of Henryk Grocholski (from a photograph), of Róża Zamoyska née Potocka, wife of Stanisław, and of Stanisław Zamoyski (copy of Jan Zasiedatel’s original, by Andrzej Mniszch), and also a self-portrait by Tadeusz Grocholski.

The portraits by unspecified authors included the likenesses of: pope Pius IX, Karol Belina-Brzozowski (father of Ksawera Grocholska), Szczęsny Potocki, Remigian Grocholski (took part in the Battle of Vienna in 1683), starost Michał Grocholski (son of voivode Marcin), Felicja Marianna Grocholska née Ślizień, Ludwik Grocholski (also son of the voivode of Bracław), Adam Myszka-Chołoniewski (castellan of Busko), Salomea Chołoniewska née Kątska, wife of Adam (considered “beautiful”), Ksawery Chołoniewski, Ignacy Chołoniewski, Adam Józef Chołoniewski and prince Stanisław Chołoniewski (brother of Emilia Grocholska, wife of Mikołaj). Another group was composed by copies of the works of great painters, or portraits painted by the master of the house, Tadeusz Grocholski: copy of Titian’s Matka Boska Bolesna (Mater Dolorosa), of also Titian’s Św. Jan Chrzciciel z Barankiem (St. John the Baptist and the Lamb), and among likenesses, the portraits of the brother of Tadeusz, Stanisław Grocholski, sister – Helena Brzozowska née Grocholska, wife Zofia Grocholska née Zamoyska, wife of Tadeusz, children – Tadeusz, Remigiusz, Michał, Ksawery and Zofia, plus studies of “peasant girl from Pietniczany”, “girl” and “girl standing by the river and drawing water”.

In the group of miniatures, two were signed by Jan Nepomucen Ender.

They depicted Henryk Grocholski and his wife Ksawera née Brzozowska, while other: Ksawery Myszka-Chołoniewski, Ignacy Myszka-Chołoniewski, nun of Visitation – Maria Cecylia Myszka-Chołoniewska, Felicja Marianna Grocholska née Ślizień, wife of Michał, Otylia Grocholska née Poniatowska, wife of Adolf, Kamilla Chołoniewska née Czetwertyńska, wife of Józef Adam, Natalia (?) Naryszkin née Czetwertyńska, Maria Czartoryska née Grocholska, wife of Witold – at a young age, Stanisław Grocholski at similar age, Tadeusz Grocholski (as a child) and Chołoniewski, first name unknown (in uniform).

In addition to the aforementioned, collections also included the following paintings: Siwy koń na łące (Grey Horse on the Meadow) by Juliusz Kossak, Polowanie na wilki (Wolf Hunt) by Józef Brandt, fifteen “Italian landscapes”, a great collection of etchings, and very many albums with own drawings by Tadeusz Grocholski. Apart from the previously mentioned, there were also two other Gobelins: Matka Boska z Dzieciątkiem Jezus (Virgin Mary with Infant Jesus) and Izraelici płaczący pod murami Babilonu (Israelites Crying at Babylon Walls), plus fifteen Polish belts by Jan Madżarski and Paschalis Jakubowicz.

The palace library ultimately comprised more than a thousand volumes. They were works in French, although some rare 16th-century editions from Kraków also were present, and even printings produced in Podolia. Many of those books had precious covers of cordovan leather, with goldened spine inscriptions and impressed ornaments. The older book collection, a religious-scientific library, created by Mikołaj Grocholski (1781 – 1864), was donated by his grandson, prince Marian Morawski, to the Frs. Jesuits to Kraków. The part that survived in Strzyżawka until the First World War, was a donation from princess Maria Czartoryska for her brother Tadeusz, made after she joined the Carmelite nuns.

The main charm of the old park of Strzyżawka, whose area together with the entire palace yards covered ca 1 sq. km., was its location on a towering, rocky Boh riverside. The park primarily stretched along both sides of the house’s side wings, creating compact greenery clusters there.

Some sections of the garden, also dotted with rocks, wre preserved in completely virgin state. The space from the main entrance avenue to the park, was open. It was shaped by a huge oval lawn. At the entrance to the forecourt, opposite the palace, stood a group of giant poplars typical of the by-Vistula areas.

There was a pavilion strictly attached to the palace, standing at its left side, until the very end called “old kitchen”.

Once the kitchen was installed in the ground level of the residential house, the pavilion was used for other purposes. It was a one-floor building, five-axial, with a southern elevation facing the forecourt, split by half-columns and panels complete in semicircular form, comprising rectangular doors and windows. The frontal façade was crowned by a wide profiled cornice. Above this building towered a belvedere with a big semicircular window, also completed by a very noticeable profiled cornice. The northern elevation of the “old kitchen” allegedly had a semicircular form. This pavilion was directly connected to the new kitchen by an underground corridor.

The wide avenue, perpendicular against the entrance avenue, leading from the state forecourt between the annexe and the kitchen, led to the church, also connected to the residence, simultaneously separating the park from farm buildings. The church stood close to the palace, but on the other side of the public road.

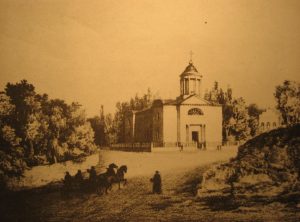

The Strzyżawka Church dedicated to Mater Dolorosa, called “extraordinarily beautiful” and “purely Italian” by Chłopicki, was founded by Mikołaj Grocholski in 1827. It was consecrated in 1838 by the bishop of Kamieniec, Mackiewicz. The architectural design of this small but interesting church, allegedly was made by the same architect who built the palace. It was constructed on the base plan of rectangle. The façade was accentuated by a surface wall break, split by panels, complete by a triangular frontage, with roof supported on kragsteins. The main entrance was framed by a hollow portico, composed of two Tuscany columns. The longer side elevations on both edges also featured one-axial breaks, completed by semicircular frontages. The apse had a triangular form, too. All strongly horizontally fluted elevations, under the crowning kragsteins, were encircled by a frieze with triglyphs and rosettes in metopes, identical as those in the portico of the palace. The body of the church was dominated by a small tower in the form of a neat gloriette, surrounded by small Ionic columns, with sphere and cross on the top.

The interior featured only one nave with an arched vault, and sixteen similarly vaulted windows on two storeys. There were three altars. The central, adorned with six white stucco columns, featured a large painting Mater Dolorosa, represented as a standing figure, with bended hands and sword plunged in chest. On the sides, against a black velvet background, numerous votive offerings were hanged. The balustrade in front of the romanica, initially wooden, was replaced by Tadeusz Grocholski with a white made of marble, better harmonised with all elements.

Also the mensa, finished with goldened tabernacle, was made of artificial marble.

In the right side altar there was a painting of The Holy Family, and Wieńczenie Chrystusa cierniową koroną (The Crowning with Thorns) to the left. All painted by Thumer, a disciple of Friedrich Overbeck. They were brought from Italy by prince Stanisław Chołoniewski, brother of Emilia Grocholska, wife of Mikołaj. The walls of the church were covered by stucco with low reliefs. Eight gypsum urns stood on cornices, anpther four – above them. The floor featured stone plates. The decorative pulpit was obscured from the entrance by a Gobelin curtain. Opposite the pulpit to the right, there was a large painting Assumption of Virgin Mary, copy of Murillo, by Jan Zasiedatel.

Station pictures etched in satin were protected by glass.

Doors situated to the right of the great altar, led to the connecting room which contained chests of drawers, filled with copes and chasubles. Over the door to the sacristy a portrait in golden frame of the founder of the church was hanging, painted by Tadeusz Grocholski. While in the interior of the sacristy, on side of a large cross, portraits of bishops were suspended on walls. On the left side of the great altar there was a door to the chamber used on Easter Friday as a “dark room”. A presbytery and bell tower stood by the manor church.

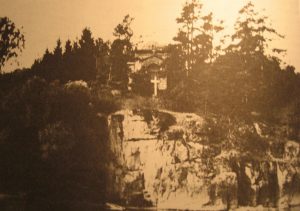

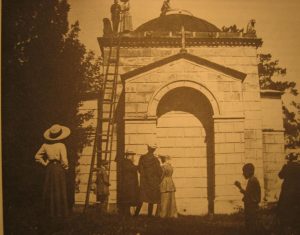

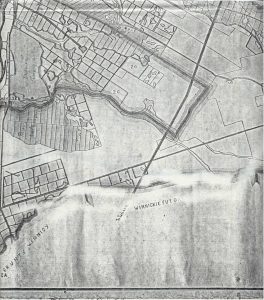

Tomb chapel. In the forest, on a high granite rock, protruding into the middle of the Boh river, there was a chapel – mausoleum of the Grocholski family from Strzyżawka and Pietniczany, erected according to the design by architect Laeufer.

It was based on a rectangular plan, with wall breaks on sides and front. The frontal break was designed to comprise the main entrance door, complete in semicircular form. All elevations of this building were rusticated and crowned by a kragstein cornice. The windowless chapel was topped by a cupula with drum provided with windows, illuminating the interior from above. The bodies of deceased heirs of both localities were entombed in the cellars, until in 1832 the Tsarist authorities liquidated the Order of Dominicans in Winnica.

Family tombs of the Grocholskis until then were located in the cellars of the monastery, founded by Michał Andrzej Grocholski, district judge of Bracław.

The entrance door to the chapel was closed using a big stone plate, devoid of any sign. Only once it was removed and a dozen or so steps were followed downwards, an iron door was approached, behind which the proper tomb was situated. It was comprised by an extensive hall carved in rock, with alcoves for coffins. There was place for 20 in the upper row plus 20 in the lower. This building long stood walled in, for its use as a chapel was forbidden. Only in 1866 permission was granted to deposit in its basement the body of the then deceased Henryk Grocholski, followed in 1872 by his wife Ksawera, founders of the chapel. Afterwards in 1888, as a result of many efforts in this regard, the Russian authorities gave their approval to move from the Strzyżawka cemetery the body of Michał Grocholski, starost of Zwinogród. At the same time also the remains of the young son of Henryk Grocholski, Władysław, were moved. The ceremony, nevertheless, had to be performed in secret, even the local parish priest could not participate.

According to the regulations in force, the entrance to the mausoleum had to be permanently walled off until 1905, when Tadeusz Grocholski managed to gain from governor Euler approval for arranging a door from the side facing the Boh river. However, with the reservation that nothing could be furnished inside, resembling Catholic rites.

Nevertheless, on walling in this mighty door, builders took the opportunity to lay a floor from white marble inside the chapel.

However, for the time being it was impossible to include a normal altar. Thus Tadeusz Grocholski painted a natural size figure of crucified Christ on a copper sheet (according to a photograph of Bonnat’s painting) and used it to adorn the then empty interior.

At the same time, a wooden cross was put opposite the door, also with a figure of Christ. Finally, another several years later, Grocholski was given the long-awaited permission to erect an altar, what again was to be done in a confidential manner.

The altar, made of white marble in Odessa, according to the design by Tadeusz Grocholski, strongly enhanced the chapel character of the family mausoleum, but the authorities’ consent to celebrate requiem mass in the same for the deceased entombed there, was obtained only as a result of several more years of efforts and applications.

Such mass could ever since be celebrated on the anniversary of the death of each person, buried in the chapel. In 1907 the body of Stanisław Grocholski from Pietniczany was deposited there, followed in 1913 by his brother Tadeusz from Strzyżawka, who had dedicated so much effort to the chapel.

During the Russian revolution, Tadeusz count Grocholski, Jr. (1887 – 1920), son of Tadeusz and Zofia née countess Zamoyska, managed to transfer family portraits to Winnica, where some Russian, willing to save cultural historical assets from the manor houses of the region from complete destruction, established the “National Museum”.

Only the library and etchings, including copies dating back to the 16th century, were stolen on the way to Winnica, taken away by train, and then somewhere into Russia, where they disappeared.

On 18th January 1918 the palace in Strzyżawka was plundered and burned down. Only the remains of the once beautiful park and the walls of the church – partly in ruin, turned into a storage facility – survived there in posterior decades. In the same year as the palace, also the tombs in the mausoleum by the Boh river were plundered. In 1920, during the Polish Army’s advance to Kiev, Henryk Grocholski collected the family portraits from the museum of Winnica, and took them to Warsaw. The objects thus saved included a bust of Julia Poniatowska née Grocholska, a mahogany chest of drawers with ornaments of goldened bronze, encrusted with medals and comprising hidden drawers for especially precious numismatic items, a mahogany table with legs ended by hoofs and ram heads supporting the top, an old-fashioned desk, a piano with elaborately suspended glass keys, a mahogany chair a la Recamier, a Boulle bed and wardrobe, a pair of mahogany beds with heads of lions, Saxon porcelain for 36 persons, a similar white set with goldened edges, and cristals. Everything was destroyed during the Warsaw Uprising in 1944.

There was once a beautiful Strzyżawka shrouded in legends and tales, enhanced by – among other – many mounds surrounded by enbankments, disseminated in the “Black forest”, composed of splendid ashes, oaks, wych elms, limes, elms and hornbeams, deeply immersed in bushes. The biggest of them was called “Piwniowa mohyła” (cock’s grave).

So it was said that if a cock crows on the grave, it would be the end of the world. One of those mounds was digged over and scientifically assessed before 1914. The remains of a warrior, his wife and horse, with various well preserved ornaments, such as brooches, bracelets, earrings and rings, were found inside.

Apart from the above, the manor area also comprised a Turkish cemetery established in 1877, when the palace housed a hospital for Turks, prisoners of war. Thanks to Tadeusz Grocholski’s efforts, the cemetery was protected by a deep ditch and planted around with trees. Later, the heir of Strzyżawka erected there a monument of white marble, featuring a proper Turkish sign, crowned by the Crescent with Star. When Sultan Abdul Hamid was told about it, he sent Tadeusz Grocholski the Medjidye 1st class medal with sash.

Roman Aftanazy “Dzieje rezydencji na dawnych kresach Rzeczypospolitej, województwo bracławskie” (History of Residences in Poland’s Former Eastern Borderlands, Bracław Voivodeship)

Published by Zakład Narodowy imienia Ossolińskich Wydawnictwo, Wrocław 1996